Drones and Threats: Mapping the Kremlin’s Hybrid Warfare in Europe

Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the Kremlin has regularly threatened European countries. These threats unfold in two dimensions. The first is rhetorical — verbal intimidation aimed at projecting strength and testing Western reaction, as illustrated by the November 2024 Oreshnik missile launch. The second is hybrid — actions that include sabotage, espionage, assassination plots and airspace violations. OpenMinds analysed 58 cases of airspace violations and hundreds of verbal threats by the Kremlin’s officials to assess the current phase of Russia’s hybrid warfare strategy.

In October 2025, Lithuania saw all kinds of flying objects in the sky besides civilian planes. First, there was a swarm of air balloons launched from Belarus on October 4. Then, on October 23, there were Russian fighter jets over Kybartai, a town bordering the Kaliningrad region. Finally, on October 24-26, there were air balloons once again — it caused the closure of Vilnius and Kaunas airports. The incident led Lithuania to shutting down the border with Belarus for a month.

Lithuania is not alone in encountering airspace violations. During this autumn, Russian military planes breached the skies of Estonia, Poland, and Norway. Apart from planes, drones are noticeable too, with September 2025 being the most prominent among similar cases — a drone incursion in Poland on September 9-10.

The reactions that followed show that Europe perceives Russia as a real threat. Poland’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Radosław Sikorski, framed it as a “deliberate provocation” and even called NATO to impose a no-fly zone over Ukraine. Some time later, at the beginning of October, the European Parliament adopted a resolution that encourages initiatives to shoot down Russian airborne targets. Finally, EU leaders are working on a mechanism known as a “drone wall” that will enable member states’ capabilities of detecting and eliminating Russian drones.

Airspace violations of European countries have become more and more regular throughout the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Since 2022, we have identified 58 such incidents. 36 incidents occurred throughout 10 months of 2025 — this is 1.6 times more than cases during the 2022-2024 period combined.

While some episodes might have resulted from accidents, such as drone debris falling on the territory of European countries after being shot down by Ukrainian anti-aircraft systems, others appear to be deliberate, as with the Polish and Lithuanian case. Security analysts agree that Russia thus aims to test collective security mechanisms within NATO. Apart from the kinetic domain, there is a cognitive aspect to it as well — experts say that cases such as drone incursion into Poland are parts of a wider intimidation strategy.

What Does the Kremlin Have to Say?

During the 10 months of 2025, publications about the incidents increased by 70% compared to all of 2024, even without counting the drone incursion in Poland, which stands out as an anomaly in terms of extensive media coverage. Out of 58 cases, 45 were represented in the media. In most cases, pro-Kremlin federal media directly cite original reports about incidents, pointing to Russia’s involvement. The only difference compared to Western primary sources is the usage of words like “allegedly” or “supposedly,” like with the case of Russian jets violating Estonian airspace.

Kremlin officials commented on 10 episodes, ignoring the rest. We counted only statements by high-ranked officials from the Kremlin, omitting claims by Russia’s ambassadors. High profile officials started actively reacting to them only recently — 8 of the incidents happened this year. This increase is most likely linked to the general focus on the topic in public and media discourse. Earlier incidents may not have provoked such a strong response simply because the violations were less blatant, thus failing to attract public scrutiny or political pressure.

Half of the comments contained denial of Russia’s involvement in the incidents (53%). Mostly, these are comments from either Peskov or MFA’s spokesperson Maria Zakharova. For example, even with evident cases such as the drone incursion into Poland, Zakharova stated that the West intentionally blamed Russia for it, although there had not been a “proper investigation.”

30% of the comments were neutral — in them, Russian officials mention a particular incident without emotionally-heavy words or any other relevant markers. For example, Peskov made such claims in relation to the drone incursion from Peskov: “The Kremlin has no new comments on the drone incident in Poland and has nothing to add to the Defense Ministry's statement.”

In 10% of the comments Russian officials made implicit threats. For instance, after one of the episodes with Russia’s drone debris falling in Romania in July 2024, a representative at the UN, Vasily Nebenzya, said that Ukraine should consider the “peace plan” voiced by Putin — “Ukraine will not get anything better.”

The smallest portion of the comments, consisting of 5%, was represented by Russian officials readdressing comments to someone else or claiming that they are not familiar with the matter. This happened with Peskov saying that the Kremlin does not know of requests for contacts from the Polish government after the drone incursion in September 2025.

Kremlin officials have also commented on other incidents of the hybrid war beyond airspace violations, including resonant cases such as assassination plots or sabotage across the EU. The reaction distribution is similar to that of airspace violations and GPS jamming cases with one difference — jokes. While remarks on airspace and navigation disruptions remain mostly formal, other incidents occasionally prompt ironic comments. For instance, in November 2024, commenting on the telecom cable between Finland and Germany being damaged, head of Russia’s parliament defence committee, Andrei Kartapolov, said that a “sawfish” is to blame.

Threats Everywhere

While the Russian government mostly either ignores or rejects its involvement in airspace violations or other hybrid war incidents throughout Europe, they do not hesitate on verbal threats of military nature and demonstrations of force.

From time to time, Russia’s army tests nuclear weapons and threatens to use them. In addition to it, the Kremlin aims to expand its military presence in the Arctics. Finally, Russian officials regularly threaten to use conventional weapons against European countries. Overall, after a brief “thaw” during the first six months of Donald Trump’s administration and a relatively smaller number of threats, Russian officials appear to be returning to the strategy of intimidating the West. The threat mentions are referred to as “threats” below.

In October 2025 alone, there were 13% more military threats than in the July-September period combined. During October, there were two events accompanied by threats of military nature. First, there was a test of the Burevestnik missile, which is capable of carrying a nuclear warhead. Maria Zakharova labeled the development of the missile as a “forced” measure. Another event was a test of an underwater machine Poseidon — as Medvedev said, if “tested against Belgium,” the country would cease to exist. Another visible part of October’s threat agenda were reactions to the news about possible supply of Ukraine with Tomahawk missiles — Medvedev mentioned hitting European capitals as a response.

The most prominent category consists of threats involving the use of conventional weapons against the West, which accounted for 38% of all publications. Then, there were nuclear rhetorics in 21% of cases.

In October 2025, the number of threats involving nuclear escalation reached its highest level of the year, following Putin’s announcement in September 2024 of changes to Russia’s nuclear doctrine. After the doctrine’s revision, the Kremlin began modelling scenarios of an all-out war with the West. Following the Burevestnik test, Russia’s Ministry of Defence claimed that the missile could be used against U.S. aircraft carrier groups, adding to Putin’s description of the test as a “great achievement” of the Russian defence industry.

Another category includes threats to deploy weapons in certain regions in response to “aggressive” policies, accounting for 17% of the publications. In 2025 alone, Russian officials announced plans to raise number of soldiers in the Arctics, mentioned responding to NATO with the deployment of new long-range missiles, and declared changes to military security on Russia-Finland border.

Other types of threats include mentions of new military developments, drills of the Russian army, and missile tests, from Sarmat tests in April 2022 as a “gift to NATO” to the recent Burevestnik test.

While incidents such as airspace violation and sabotage are often left uncommented by Russian officials, threats from them mostly come as reactions to events related to Ukraine’s weapons supply. However, the strategic goal seems to be the same — disrupt the unity of Ukraine’s allies at all cost, either by sending drones over neighbouring countries or boasting the capabilities of new missiles reaching NATO’s “decision-making centers.”

Russian officials and pro-Kremlin experts talk more and more often about expanding the geography of the war against the West. What started as single isolated events of drone and missile debris falling in Romania or Poland now becomes a deliberate and complex tactic consisting of airspace violations, sabotage, assassination attempts and espionage.

Methodology

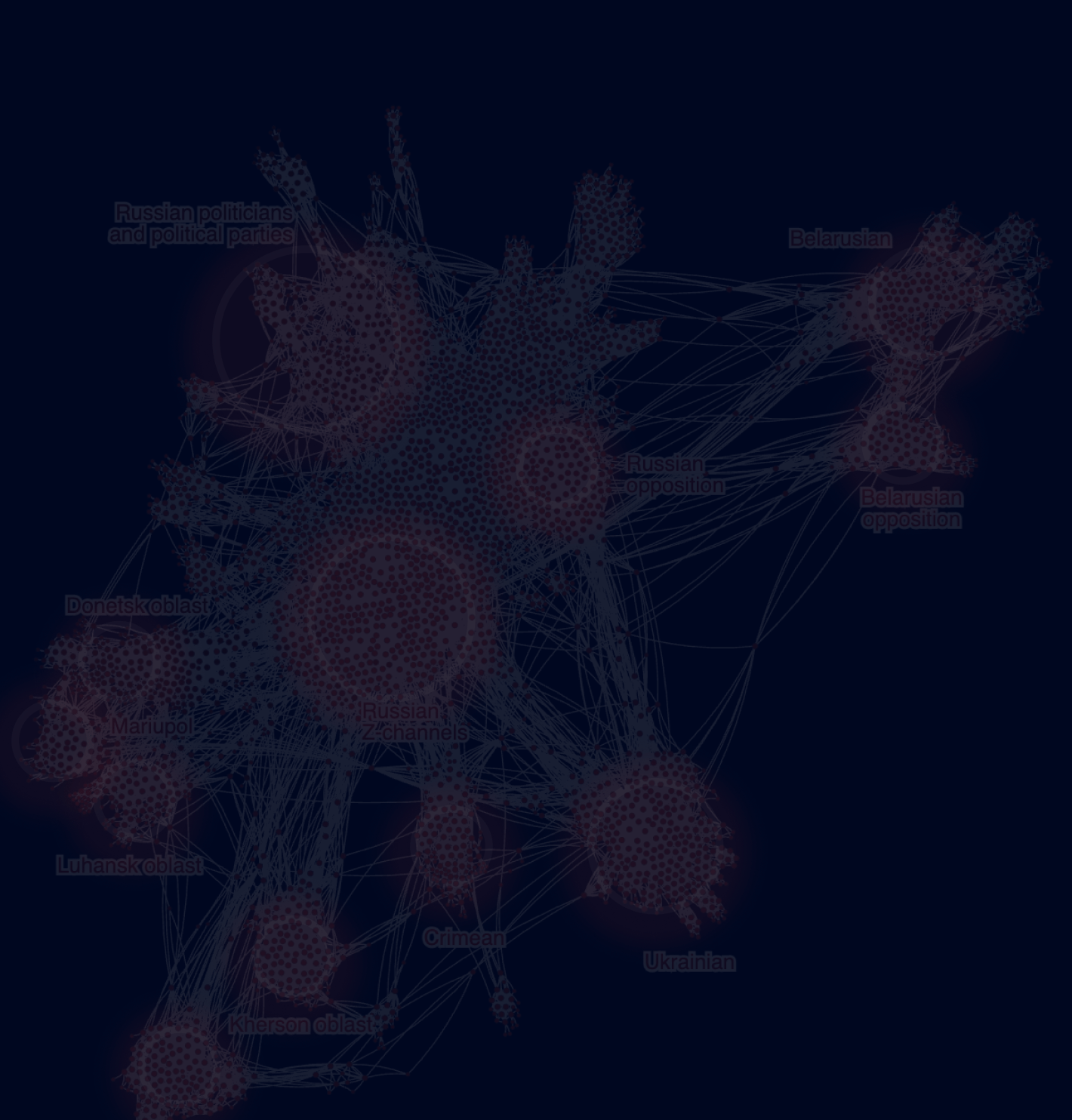

To assess the reaction to the incidents, we collected more than 4.4 million publications from 99 popular political Telegram channels (including Russian media outlets, bloggers, politics experts, and war correspondence channels) for the period from January 1, 2022, to October 30, 2025.

The incidents of airspace violations were collected from numerous open sources and Wikipedia. Besides airspace violations, we collected data on other incidents from the International Institute for Strategic Studies’ report The Scale of Russian Sabotage Operations Against Europe’s Critical Infrastructure. We narrowed the initial dataset by applying a filter of a day of the incident and three days after it to cover the period during which the reaction to it might be issued.

Using a large language model (gpt-4o-mini), we filtered out irrelevant publications and identified the rhetorical strategy used to react to the incident. We listed 5 rhetorical strategies:

- Threats: the incident is mentioned but accompanied by intimidation, shows of force, or escalation

- Neutral: factual description mentioning Russia’s involvement, without evaluative language.

- Denial: denial of Russia’s involvement, claims that the incident is fake or a provocation.

- Irony: use of mockery, sarcasm, or exaggeration of accusations.

- Unknown actor: the event is described without naming a culprit, e.g., “unknown drones.”

To assess the military threats, we collected more than 1.2 million publications from 10 popular Telegram channels for the period from January 1, 2022, to October 30, 2025. By applying keywords and phrases such as “response,” “strike,” “sanctions,” “consequences,” “threat,” “red line,” and others, we narrowed the dataset.

By military threats, we refer to statements promising concrete military actions in response to enemy's actions that had not yet been implemented at the time of the statement. Additionally, we include the coverage of real-world military activity such as missile tests.

Using a large language model (gemini-2.0-flash), we filtered out irrelevant entries and identified key elements: the “threat source” (such as a person or country from which the threat originates), the “threat reason,” the “threat description,” the “threat target” (who the threat is directed at), “threat target country”, and the “threat category”. The categories are listed below:

- Nuclear escalation: Direct or indirect threat of using nuclear weapons.

- Conventional strike: Direct threat to carry out an attack using conventional (non-nuclear) weapons.

- Military deployment: Threat through troop or equipment redeployment, or establishment of new military bases near borders.

- Missile test: Threat expressed through test launches of missiles or trials of other weapons systems.

- Military exercise: Threat through the organization of large-scale military drills near the borders of a potential adversary.

- Development: Threat related to the development, upcoming deployment, or production of new or improved weapons systems, accompanied by an explicit warning.

- Other: Any other military threat not covered by the categories above. Used only as a last resort.

.svg)

.jpg)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

-01-2.avif)

-01.avif)

-01.avif)

-01%25202-p-500.avif)