Reset That Failed: Russian Threat Index Rises for Third Straight Month After a Brief Thaw

At the beginning of 2025, Russian officials threatened Ukraine and the West surprisingly rarely. Considering the newly elected President Trump and his promises to “end the war in 24 hours,” some might have felt optimistic about a potential peace settlement to Russia’s war against Ukraine. However, the latest trend shows a return to previous levels of threats and growing disillusionment on all sides. OpenMinds shares insights drawn from the Russian Threat Index, our metric that tracks the intensity of Kremlin rhetoric over time.

Intercontinental Neuroleptics

Autumn of 2024 was a period of escalation related to a permission for Ukraine to target Russian territories with Western long-range missiles. Russian officials responded with numerous threats to various countries involved, predominantly the UK and the USA. The threats involved “destroying all European military bases,” implying that the West is “walking on a slippery slope into the abyss,” “complete destruction of Russia-U.S. relations” if Ukraine uses American missiles against Russia.

Threats are among the key instruments of Russian officials’ foreign policy. We created the Russian Threat Index (RTI) to measure how the Kremlin’s rhetoric towards Ukraine and the West evolves over time. The data covers 100 key Telegram channels of pro-Kremlin media, political bloggers, experts, and war correspondents from January 2021 to the beginning of May 2025. January 2022, a month prior to the full-scale invasion, serves as the baseline of this index, with the value of 100.

This is a reassessment of the older version of the RTI with updated methodology — the “Methodology” section features a detailed description of how the data was gathered and analysed.

Despite the escalation in autumn 2024, the destruction of relations between Russia and the U.S. never happened. In January 2025, the RTI decreased to 80 points — it became the “calmest” month since February 2022. The election of Donald Trump significantly decreased the circulation of Russian verbal threats to the U.S. throughout the winter of 2025, with officials sometimes saying warm words about Trump, like praising his “self-control” or hoping that he would “instill discipline” in Europe.

However, the détente didn’t last long. The RTI has been growing since January, returning to usual levels in April 2025 — the index hit 158 points. At the end of March 2025, Russian ex-President Dmitry Medvedev compared “russophobia” to a clinical disease. He said that a significant part of European politicians have it in different “forms” — Emmanuel Macron and Keir Starmer have a “manic stage,” whereas Ursula von der Leyen and Kaja Kallas have a “depressive stage.”

He went on to suggest a “treatment” that included the names of Russian missiles. Kalibr, Iskander, and Oniks were called “sedatives,” Oreshnik a “tranquilizer,” and Yars with Sarmat were titled “nuclear neuroleptics.” Some of these missiles are routinely used against civilians in Ukraine, and Medvedev explicitly offers to continue the usage against a range of European countries.

Despite the facade greetings of negotiations and announcing “ceasefires” that are broken simultaneously, the threat towards Europe by Medvedev is a symptom of a wider phenomenon — the Kremlin does not wish for lasting peace. This is evident by the growing index value from February to April 2025 — a return to standard practice after the “verbal de-escalation” period following the Trump inauguration.

The Evolution of Threats

Before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2021, politicians regularly threatened both Ukraine and the West. They routinely accused the “Kyiv regime” of genocidal practices against inhabitants of occupied territories — examples include the so-called “water blockade” of Crimea or planning a “force scenario” against the self-proclaimed “republics” in the eastern regions of Ukraine. Threats against the West mostly consisted of diplomatic and economic ones, such as the expulsion of diplomats or reactions to sanctions imposed on either Russia or Belarus.

Right before and after the beginning of the full-scale invasion, in February and March 2022, Russian officials constantly issued threats — the RTI was 202 and 357 points, respectively. Capturing major cities of Kyiv and Kharkiv was “not an issue” in the words of Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov, while Putin stated that a no-fly zone over Ukraine would mean direct involvement in the war by third countries.

The next peak occurred in autumn 2022, particularly in October after the explosion on the Crimean bridge, when the RTI value was 276 points. Medvedev envisioned the “complete destruction of terrorists” as the only way to respond to the explosion. Another event of that time was drawing “red lines” for the West in terms of long-range missile delivery to Ukraine.

A peak in May 2023 coincided with a less verbal but more performative threat — the announcement of the deployment of nuclear weapons in Belarus. During that month, the RTI hit 237 points. Moreover, then-minister of defence Sergei Shoigu announced the deployment of additional Russian military forces in Belarus. Although officials mostly stated that Russia had no plans to use nuclear weapons, some bloggers denounced the official narrative, claiming that Russia should not be “more saint than the Pope.”

Spring 2024 was marked by threats toward France because of Emmanuel Macron’s idea to send peacekeeping forces to Ukraine, and claims that F-16 delivery to Ukraine is a just cause to use nuclear weapons. The RTI during March and May 2024 was 248 and 260 points.

The latest index spike occurred during autumn 2024, with RTI hitting 244 points in September and 240 in November. The rising index related to talks about allowing Ukraine to strike Russian regions with Western long-range missiles, such as ATACMS and Storm Shadow. In September, the head of the Russian parliament’s defence committee, Andrei Kartapolov, claimed that an allowance like that will untie Russia’s hands in the usage of nuclear weapons. In November, Russia launched the Oreshnik missile against Ukraine — a missile compared to a nuclear weapon by Putin.

Now, although Western countries face fewer threats than before and the majority of them are aimed at Ukraine, there is still evidence of a hostile narrative targeting both the US and the EU. For instance, Russian officials claimed that the potential usage of Taurus missiles by Ukraine would mean Germany’s “direct participation” in the war. Another threat involved implying that Poland and the Baltic states would be “first to get hurt” if NATO “invades” Belarus or Russia. Another set of threats came from Shoigu. Peacekeeping forces in Ukraine (or, as he puts it, “historical Russian territories”) would mean the start of “World War 3” and that Russia will conduct a nuclear exercise as a response to “analogous U.S. activities.”

Kremlin’s Threat Arsenal

The Kremlin has various threats in its arsenal that we have identified. Military threats are the biggest group that make up more than 55% of the sample. They mostly include statements by officials regarding combat against Ukraine, such as Putin’s remark in March 2025 that “the main challenge” is to “destroy the AFU in the Kursk region in the near future.”

The second biggest category consists of economic threats (10%). Russian officials are concerned about the frozen assets that are used by the West to provide aid for Ukraine. In March 2025, Putin’s press secretary, Dmitry Peskov, claimed that this procedure is “illegal” and will have “serious legal consequences” in the future. Another hot topic was rumours about Western companies returning to the Russian market. However, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that Russia is not “rushing to forgive” the companies in question.

Abstract threats (9%) come next. They mostly do not contain any particular indications of actions, but instead focus on phrases like “asymmetric responses” “red lines,” and other terms used to signal strength through language. At the end of March 2025, Russian MP Leonid Slutsky claimed that Ukraine regularly breaks the “ceasefire agreement,” and that is why Moscow would answer “symmetrically.” There was a spike in abstract threats in June 2024 when Ukraine used ATACMS missiles attempting to hit Russian military targets in Sevastopol. Russian officials framed it as a “direct participation” of the USA in the war. After the attack, Peskov promised “consequences” for such involvement.

The fourth group contains nuclear threats (8%). Mentions of nuclear weapons were prominent throughout 2024. These mentions mostly coincided with news about either the usage of long-range missiles by Ukraine or getting permissions from Western allies to use the missiles to strike within Russian territories. This featured performative threats and their highlighting, such as drills of nuclear deterrence units in the Russian army in November 2024.

Diplomatic threats (5%) are the smallest group in the sample. Mostly, they feature reactions to diplomatic conflicts with other countries. For example, in March 2025, Russian law enforcement designated two British diplomats as spies. During the episode, the Russian MFA warned the UK against “further escalation,” claiming that Moscow would not tolerate unauthorised secret service activity. This works another way as well. In October 2024, Norway demanded that the Russian consular presence be reduced. Afterwards, Russian MFA’s spokesperson Maria Zakharova promised “responsive measures.”

Also, there is an uncategorised group of threats (13%). The recent examples include Lavrov’s words that Russia would not “tolerate the resurrection of European nazism” or envisioning a future “tribunal” against the Ukrainian army by stating that Russia collects evidence of Ukrainian war crimes. Moreover, almost a third of this group is represented by announcements of new legislation in Russia aimed at suppressing local dissent, shifting threats inward.

Most countries face predominantly military threats from Russia, they constitute either a relative or an absolute majority. However, threats towards the EU were mainly of the economic category (37% compared to 26% of military threats). This is related to the sanctions the EU imposes — Russian officials tend to react with “responsive measures” and claim that Russia will cut off the gas supply to Europe.

Who Gets the Threats?

Ukraine is leading in the “rating” of targets of Russia’s threats. We detected more than 10 000 mentions of Ukraine in the news containing threats — 57% of the sample. The majority of the threats are related to combat areas, like claims about “planned annihilation” in Kursk region or announcements to destroy the Ukrainian energy system.

After Ukraine, the running-up actors are the USA (1923), NATO countries (635), the EU (626), the UK (480), and Poland (410).

The trend started to change by the end of 2024 as threats against the United States subsided. This is mostly related to softening the Kremlin’s official rhetoric towards the Trump administration.

If broken down into separate categories, peaks of threats against each country were associated with the following events:

- Finland — May 2022. The main “trigger” coming from Finland was news about it joining NATO. Russian officials threatened to target Finland with nuclear weapons, “destroying the country as a whole,” and cutting the gas supply to the country.

- Lithuania — June 2022. Lithuania banned commodities transit to the Kaliningrad region of Russia. Nikolai Patrushev, head of the Russian Security Council at the time, promised “serious and negative” consequences for Lithuania.

- Poland — April and May 2023. In April, the threats were predominantly related to Poland's “capturing” a school belonging to Russia’s embassy. Russian officials abstractly threatened Poland with “severe reaction from Moscow.” As for May, there is no distinct event that triggered threats, but a series of events. Firstly, Russian officials claimed that Poland “plans to invade” Belarus and promised to defend thecountry. Another event was a reaction to Poland’s plans to seek reparations from Russia — parliament’s speaker Vyacheslav Volodin offered to ban the transit of Polish trucks via Russia.

- France — March 2024. Macron stated that France did not have red lines in terms of aid to Ukraine.— Medvedev responded that, from that moment, Russia did not have red lines against France. Another spike occurred closer to the end of the month when the Russian officials reflected on Macron’s idea of sending peacekeeping troops to Ukraine,— suggesting a “big number of caskets” arriving back in France and accusing of provoking World War 3.

- Germany — April 2023 and March 2024. In April 2023, the Minister of Defence of Germany, Boris Pistorius, said that Berlin was not against Ukrainian combat operations on Russian territories. As a response, Medvedev threatened that “every German who wants an attack on Russia should be prepared for our parade in Berlin,” referring to World War 2. In March 2024, Russian officials reacted to the Bundeswehr interception, claiming that “denazification of Germany is not over.”

- UK — May 2024. British authorities expelled the Russian military attache. Russia responded symmetrically by expelling the British military attache. Among other threats that month were claims that Russia would hit UK military assets “inside and outside Ukraine” if the latter uses British missiles against Russian territories.

- USA — June 2024. The threats were related to the missile hit on Sevastopol, a city in occupied Crimea. Russian officials accused the U.S. of being responsible for this attack. Russia’s MFA summoned the U.S. ambassador to address that “Washington's activities will not be left without punishment.”

- Moldova — December 2024. Russian officials claimed that Moldova was planning a military operation against the self-proclaimed “Transnistria” and promised to interfere if the escalation happens.

Apart from threatening foreign countries, we observed a phenomenon of inward threats. These are directed at Russian citizens (both inside and outside the country) through similar vocabulary with legislative initiatives added to it. The latter includes the proposal to toughen up legal punishment and widen the criteria of inclusion to the “foreign agents” list — a measure used by Russian authorities to repress the opposition. Another example includes labelling Russians abroad “traitors” and suggesting to impose fines on citizens who move into another apartment without notifying the military recruitment office.

Threatening for What?

At some point, it became evident that Russia’s threats towards Ukraine’s allies are mostly empty, and subsequently, Western leaders understood that. This led to “raising the stakes” in arms delivery for Ukraine and allowing it to use long-range missiles against Russian territories. Moreover, the Ukrainian incursion into the Kursk region completely changed the situation, as it was an internationally recognised region of Russia. In the end, the “red lines” drawn and threats of a “symmetrical answer” resulted in intensified shelling of the Ukrainian Sumy region — a border neighbour to the Kursk region — with ballistic missiles, often targeting civilians.

The Kremlin’s return to its usual threats after a brief “thaw” in early 2025 suggests a clear pattern. Despite superficial gestures toward peace talks and proposed “ceasefires,” it shows no real interest in lasting peace. More likely, it seeks a short pause to regenerate its military and economic capacities.

The regime appears to feel comfortable in a “new Cold War” atmosphere, marked by diplomatic expulsions, accusations of foreign “invasion plots” in Belarus or Transnistria, and a hardline realpolitik approach. Threat-making remains central to this worldview, echoing Soviet-era tactics like Nikita Khrushchev’s promises to “bury” Western leaders or to show them “Kuzma’s mother.” Whether to mobilise the public against the “common enemy,” advance geopolitical aims and pressure Western politicians, or achieve some other goal remains to be seen — but sustainable peace does not seem to be on the agenda.

Methodology

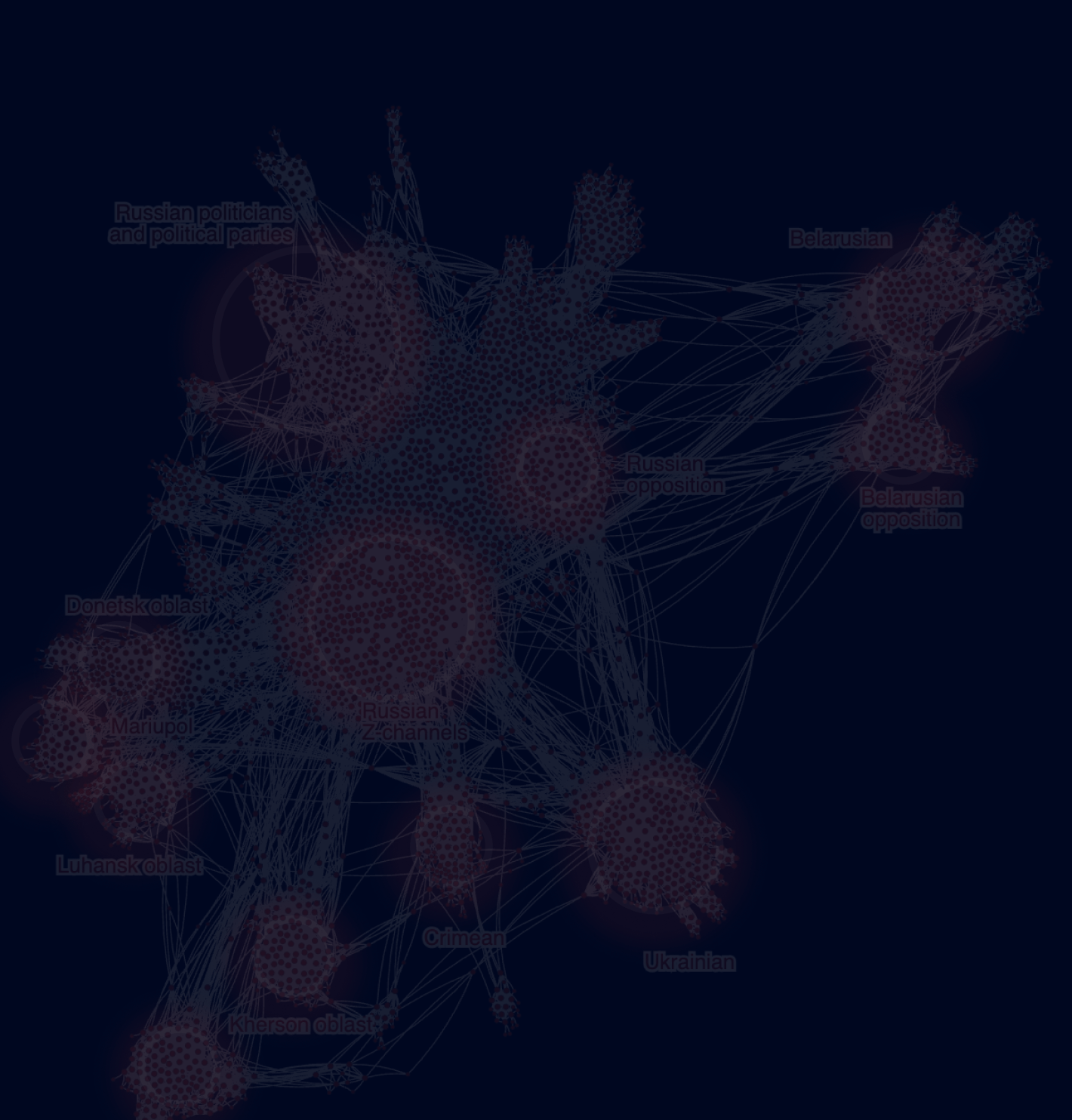

To assess the RTI, we collected more than 3.3 million publications from 100 popular political Telegram channels (including Russian media outlets, bloggers, politics experts, and war correspondence channels) for the period from January 1, 2021, to April 30, 2025.

The mentions of threats recorded each month was converted into an index, with January 2022 — the final month before the start of the full-scale invasion — serving as the baseline, set at 100.

By applying keywords and phrases such as “response,” “strike,” “sanctions,” “consequences,” “threat,” “red line,” and others, the dataset was narrowed down to 386 thousand posts referencing threats.

By threats, we refer to statements promising actions in response to an enemy's actions that had not yet been implemented at the time of the statement. Such rhetoric often includes conditional sentences or marker words like “red lines” and “symmetrical response.”

Using a large language model (gemini-2.0-flash), we filtered out irrelevant entries and identified key elements: the “threat source” (such as a person or country from which the threat originates), the “threat reason,” the “threat description,” the “threat target” (who the threat is directed at), “threat target country”, and the “threat category”. The categories are listed below:

— Nuclear: threats associated with nuclear weapons or their deployment,

— Military: threats to use military force or weapons,

— Abstract: abstract threats (statements about "red lines", promises of a "symmetrical response", vague warnings, and other vague language without specifying specific measures),

— Economic: economic threats (sanctions, trade restrictions),

— Diplomatic: diplomatic threats (severance of relations, expulsion of diplomats).

The model assessed confidence in the accurate definition and categorisation of each threat using the “confidence score” parameter. Furthermore, the authors manually verified the data.

Unlike the previous methodology, which calculated the index based solely on threats voiced by official political figures and derived from a narrow set of 10 pro-Kremlin media outlets, the updated Russian Threat Index (RTI) is based on mentions of threats across a much broader spectrum of Telegram channels. These include state-aligned media accounts, pro-war bloggers, and other influential actors within the Telegram ecosystem. This shift allows for a more comprehensive view of how hostile rhetoric is distributed and amplified in the Russian information space.

.svg)

.jpg)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

-01-2.avif)

-01.avif)

-01.avif)

-01%25202-p-500.avif)