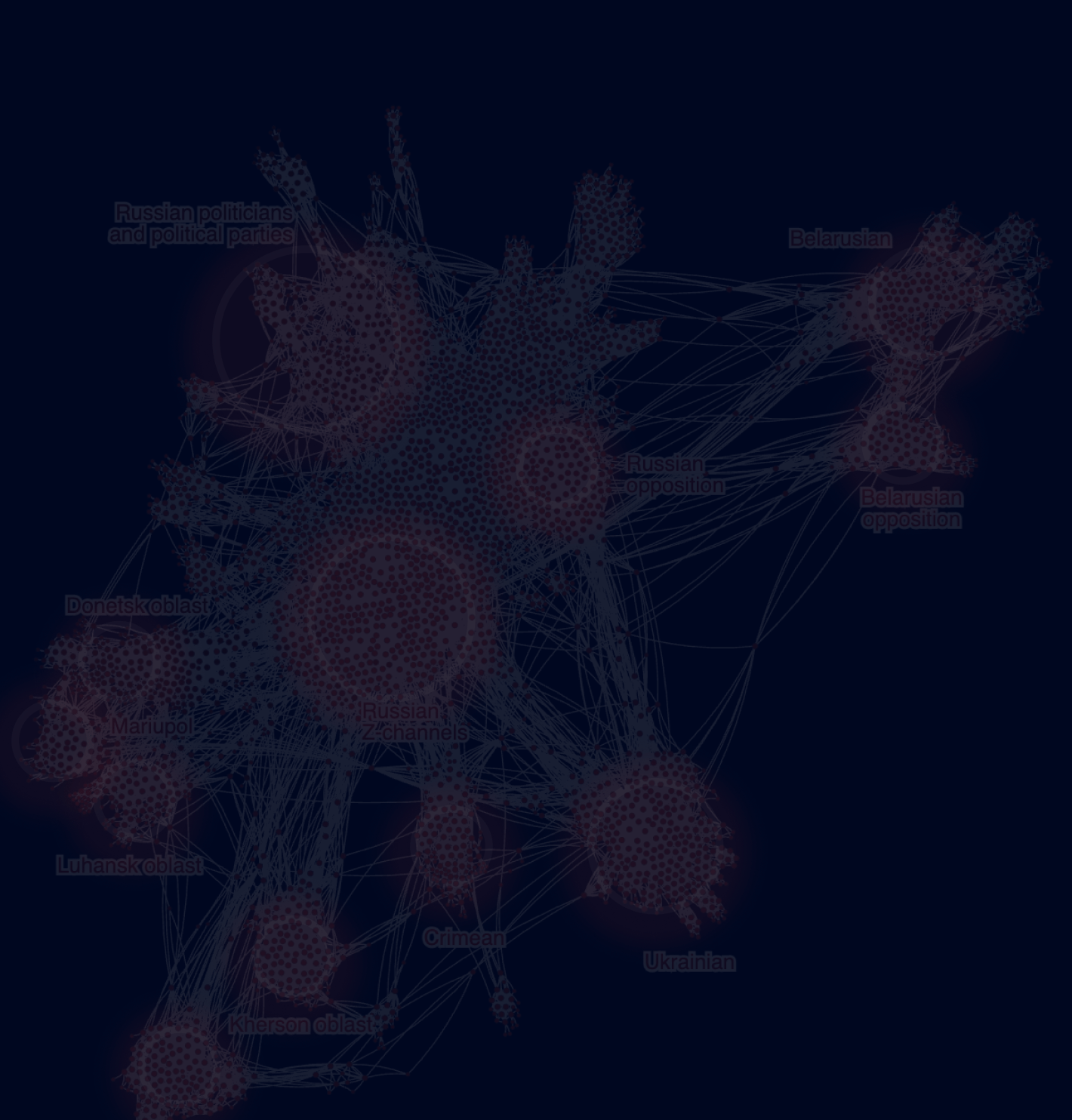

The Telegram Information Network Across Borders

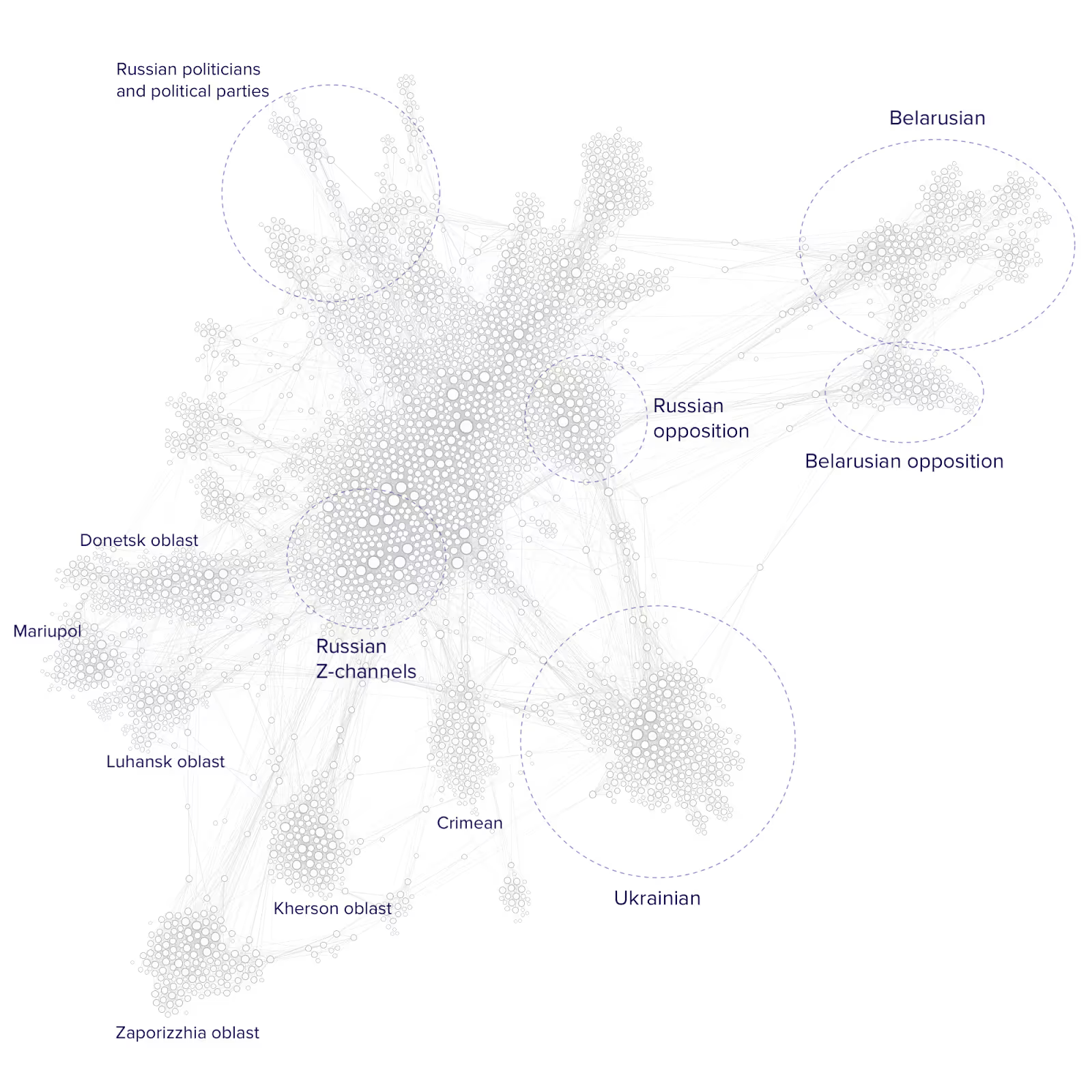

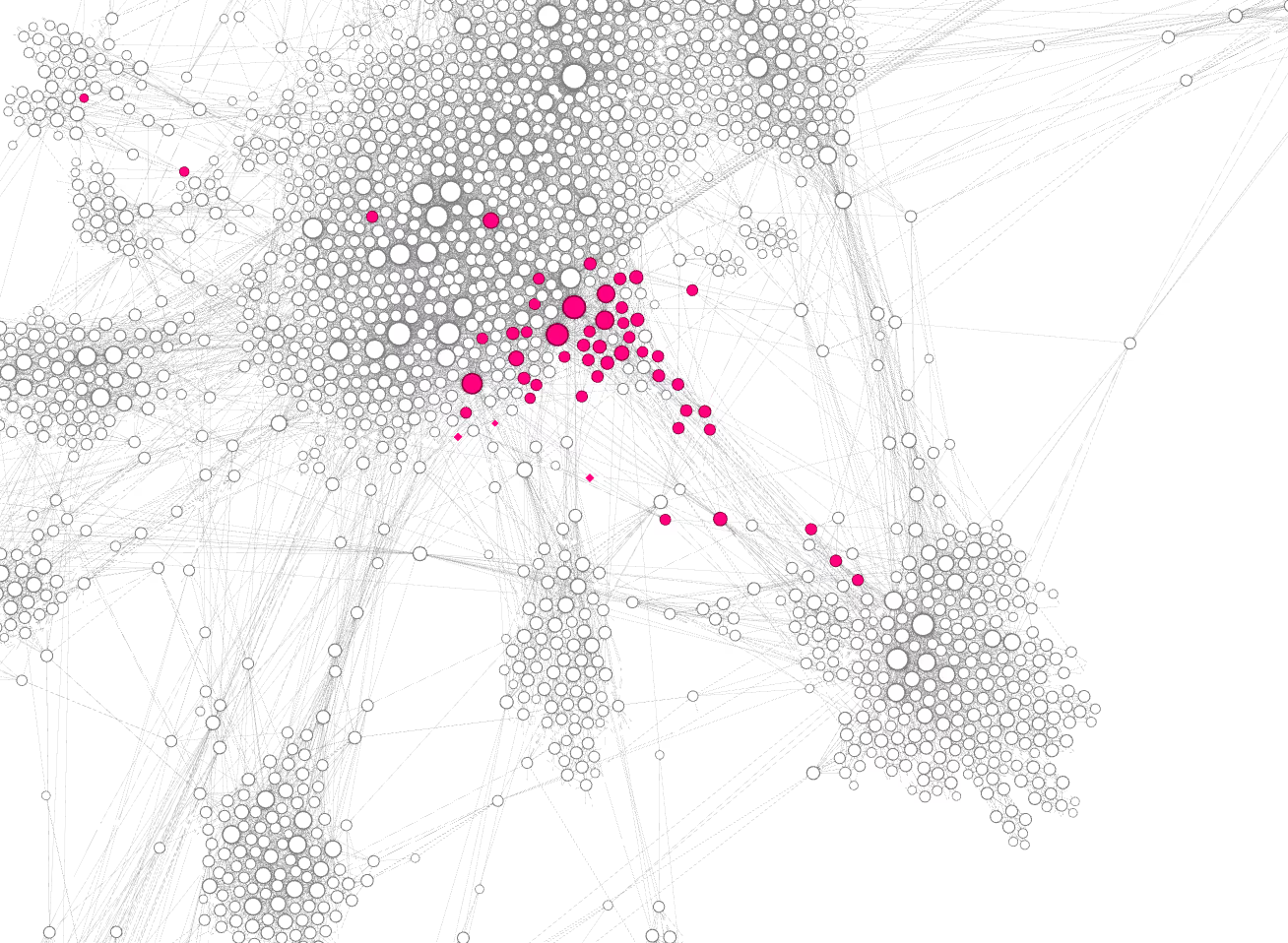

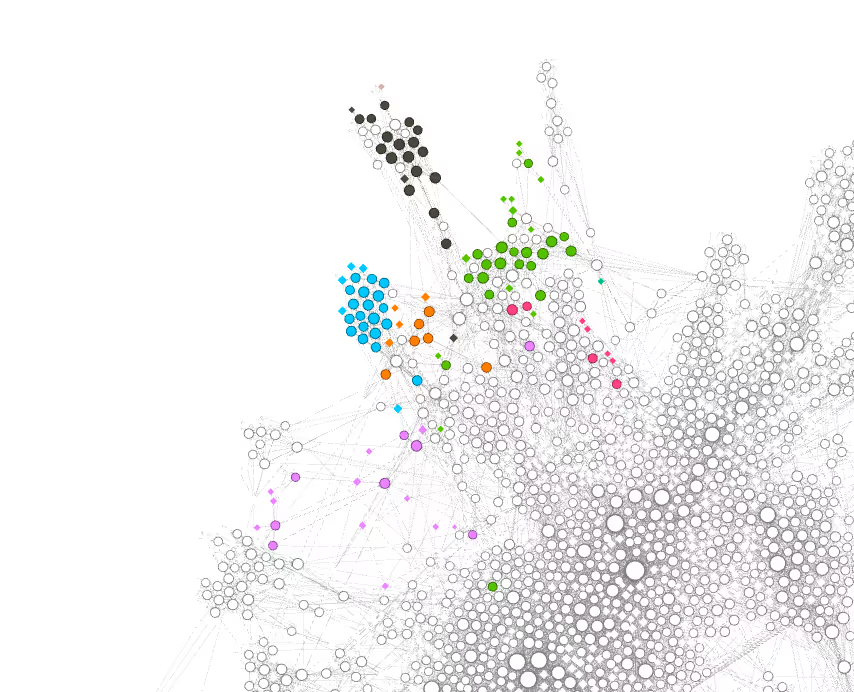

The overall network looks as follows: at its center lies a massive hub of Russian information Telegram channels. This hub contains two opposing “poles” – one formed by Russian opposition channels, the other by pro-war content, including the official Ministry of Defense channel and propaganda-heavy accounts such as “Operation Z: War Correspondents of the Russian Spring.”

At the top of the network, we find Russian political channels represented by accounts linked to local politicians and political parties.

Somewhat removed, yet still connected to the Russian hub, are clusters of Ukrainian and Belarusian information channels. The Belarusian segment, in particular, features a clearly separated opposition cluster – mostly exile-run channels, often in the Belarusian language and marked by white-red-white symbolism associated with the anti-Lukashenko resistance movement.

From the Russian pro-war cluster, ties extend to channels focused on the occupied territories – including Crimea, the so-called “DNR” and “LNR,” as well as parts of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions currently under Russian occupation. Mariupol, while administratively part of Donetsk oblast, stands out as a separate cluster due to its population size and the diversity of Telegram channels created specifically for local audiences.

Unsurprisingly, many connections in the network are organized around geography – local outlets often compete for the same regional audiences. These users, in turn, follow national or international news, where competition is steeper and the likelihood of appearing in each other’s “similar channels” list is lower. This dynamic results in a network that is both relatively well-clustered and broadly interconnected.

A more granular analysis of this structure offers valuable insights into how information ecosystems on Telegram are shaped – and how influence flows across national and ideological boundaries.

Pseudo-Ukrainian Telegram Channels

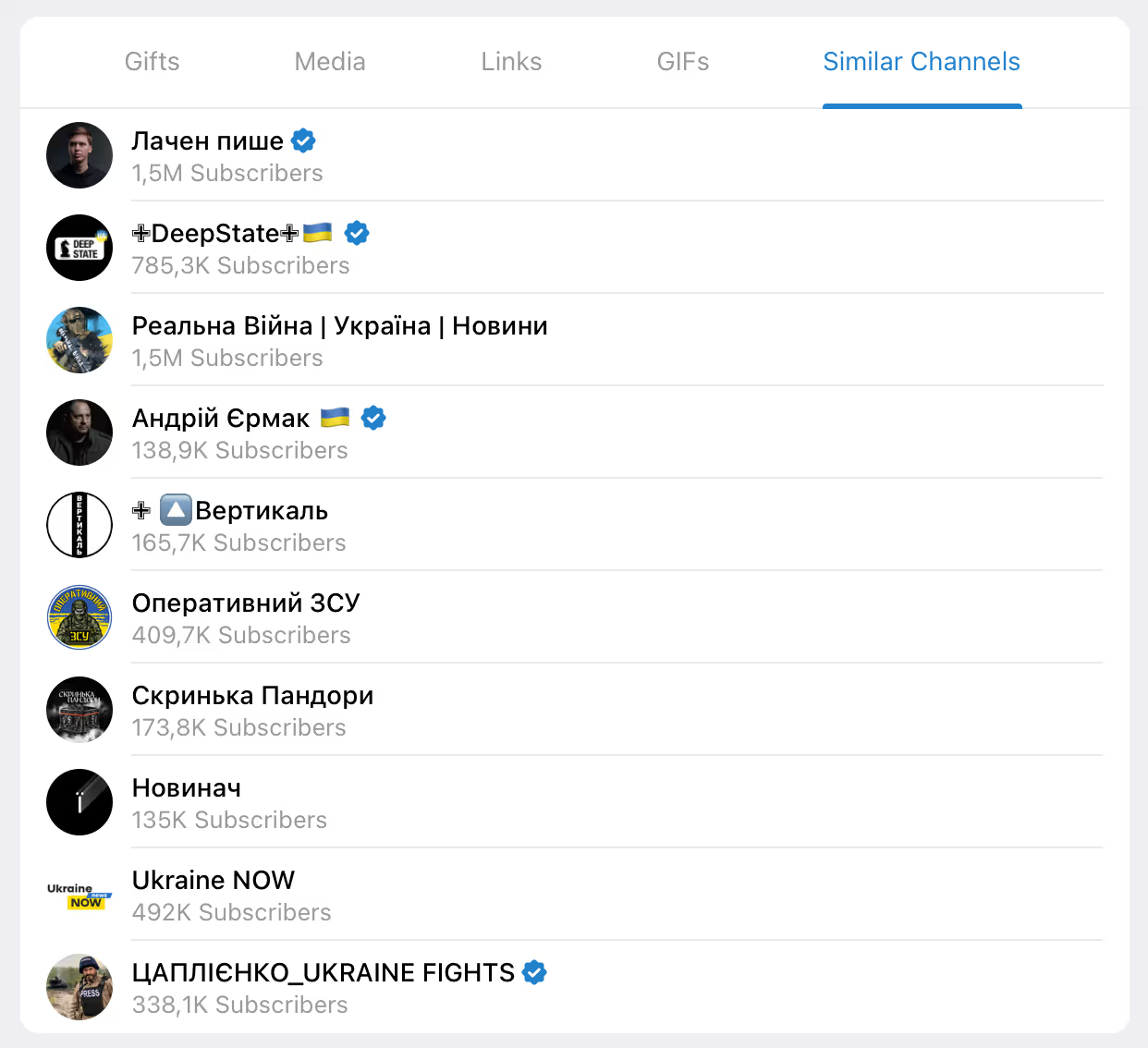

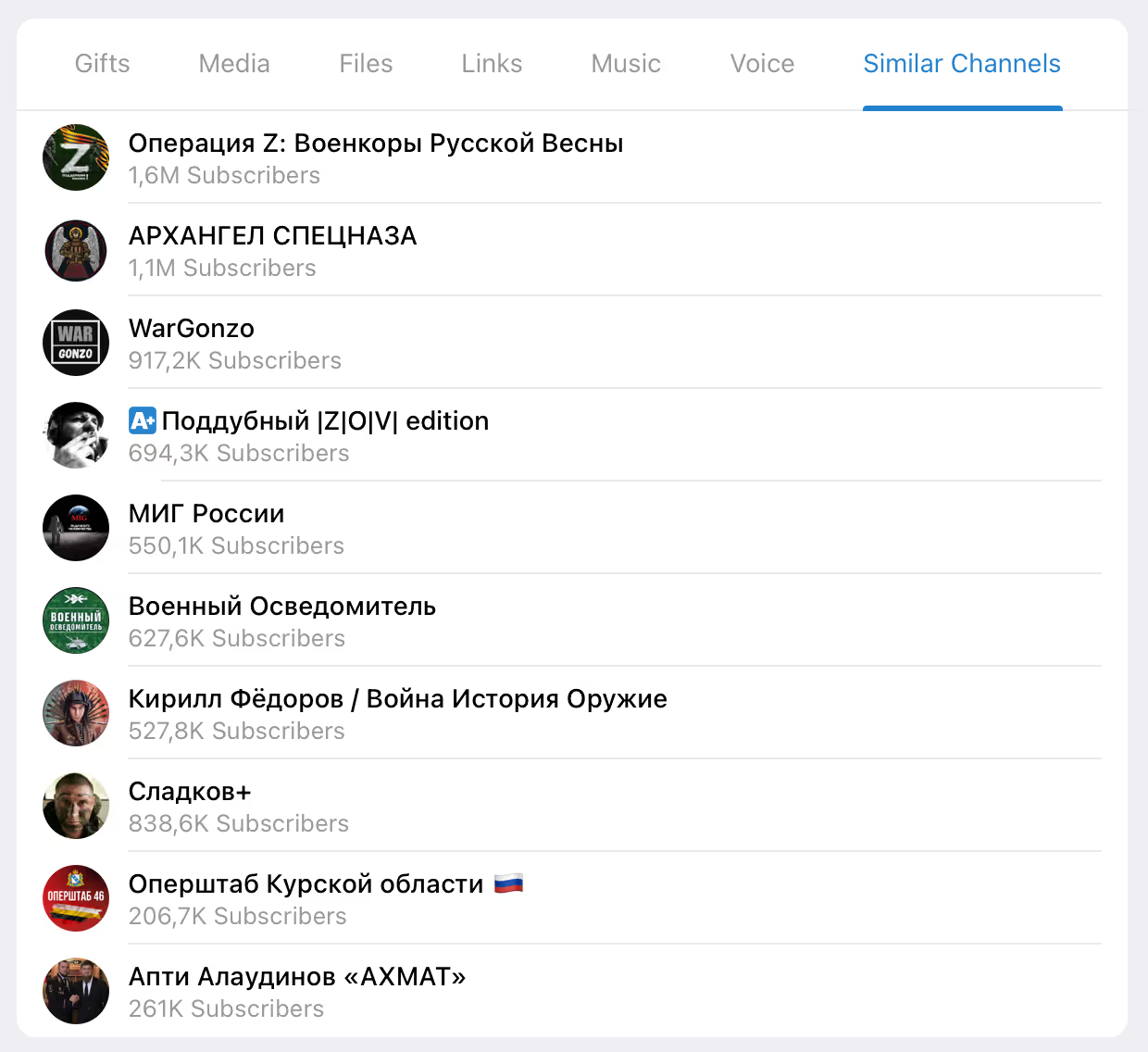

As mentioned earlier, a significant portion of the Russian information hub consists of war-related channels. These include military correspondents and bloggers, channels dedicated to specific brigades, and frontline analysis. Together, they reach an audience of more than 28.5 million subscribers.

Slightly further from the war cluster are more formal propaganda outlets like Соловьёв and Readovka. Closer to the core of the network are major pro-Kremlin national media and aggregators such as ТАСС, Mash, Раньше всех, and ЕЖ.

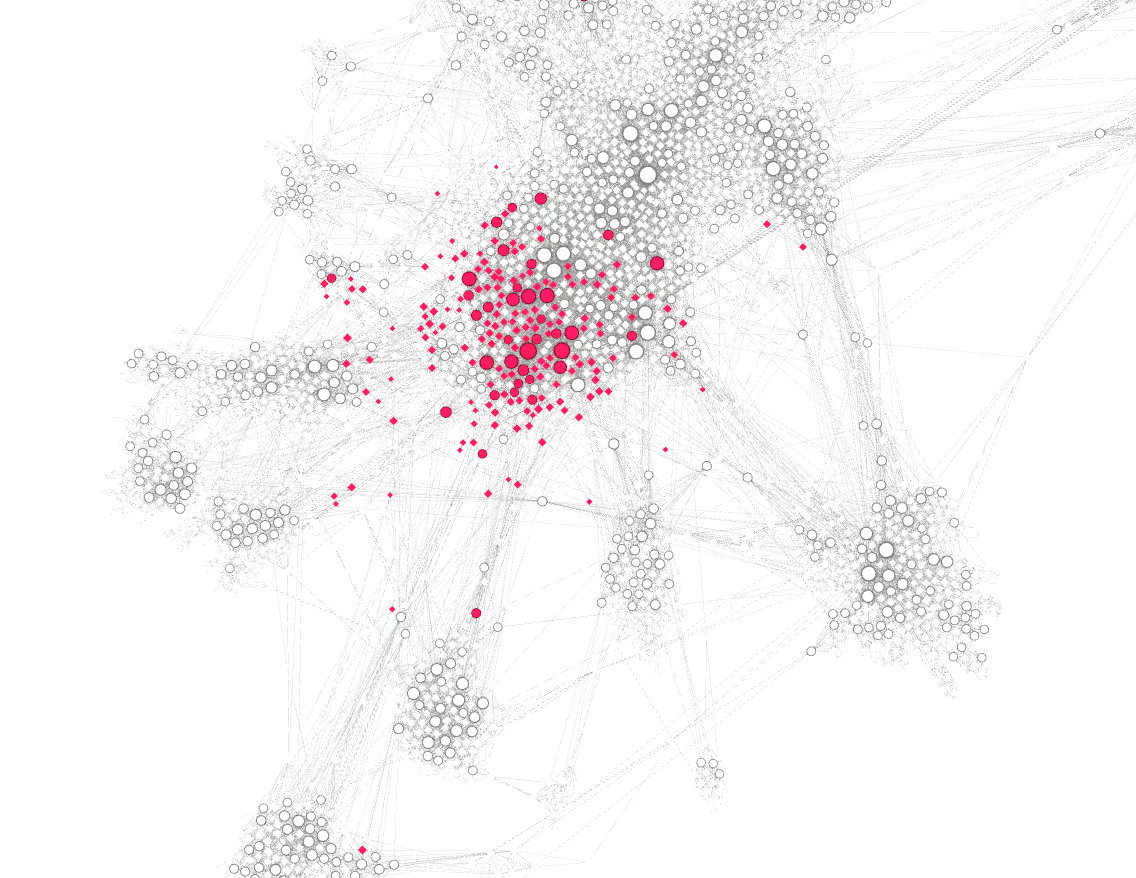

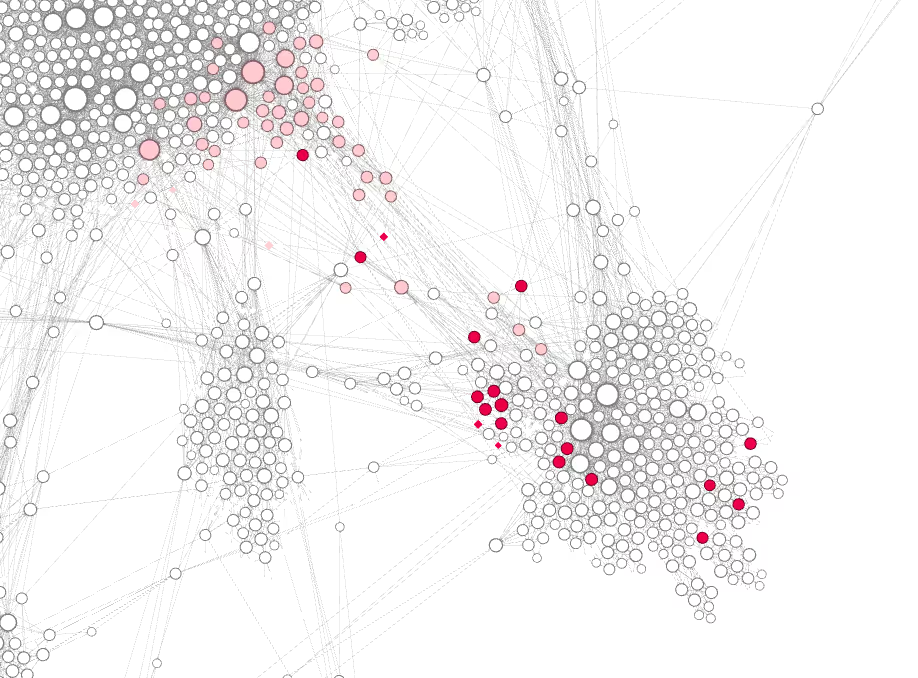

But adjacent to the war channels is another category of actors – what we refer to as pseudo-Ukrainian channels. These are accounts often launched long before the full-scale invasion, with the strategic purpose of promoting Russian narratives within Ukraine.

One notable example is Украина.ру – a media outlet under the “Россия сегодня” media group, launched in 2014 as a Kremlin propaganda mouthpiece targeting Ukrainian audiences. Today, it is among the most influential Telegram channels in this network, both by subscriber count (almost 500K as of early June) and frequency of appearance in “similar channels” lists (node degree: 115).

This group also includes channels reportedly linked to Russia’s 85th Main Special Service Center of the General Staff – such as Резидент, Легитимный, and Картель. Many others share identical anti-Ukrainian narratives or are operated by former Ukrainian MPs and politicians – now sanctioned, wanted, or imprisoned for collaboration with Russia.

Most of these channels show little to no connection to the Ukrainian Telegram cluster. Instead, they are deeply embedded within the Russian information space. This suggests that they now function more as a simulated Ukrainian “opposition” targeting Russian audiences, rather than vehicles for promoting Russian messages to Ukrainian users.

If any Russian campaign can be seen as effective in reaching its target group, it is the discrediting of Ukraine’s military mobilization. While Ukraine does face real issues in recruitment processes, Russia has worked to exaggerate and amplify individual incidents across platforms – especially within Telegram’s low-moderation environment.

This type of content is regularly disseminated both by the pseudo-Ukrainian channels described above and by newer accounts strongly connected to them – such as Ховайся. However, many Telegram channels dedicated to topics like conscription, draft evasion, or fearmongering around mobilization are much more tightly integrated into the Ukrainian Telegram cluster – and often publish content in Ukrainian.

Also closer to Ukrainian audiences is Мирослав Олешко (НОВИНИ ПРАВДИ: блог Олешко). Once an anti-vaccine activist, he is now wanted by the SBU, living abroad, and positioning himself as a leader of the “anti-mobilization movement.” He actively spreads falsehoods and Russian narratives identical to those of Анатолий Шарий – a former Ukrainian journalist turned Russian propagandist, charged with treason and on Ukraine’s wanted list since 2021. Шарий’s Telegram channel is one of the most influential in our network, with 1.4 million subscribers and 176 co-mentions across similar channels. But unlike Sharii, Oleshko appears to be far more successful at reaching Ukrainian audiences – according to his network position.

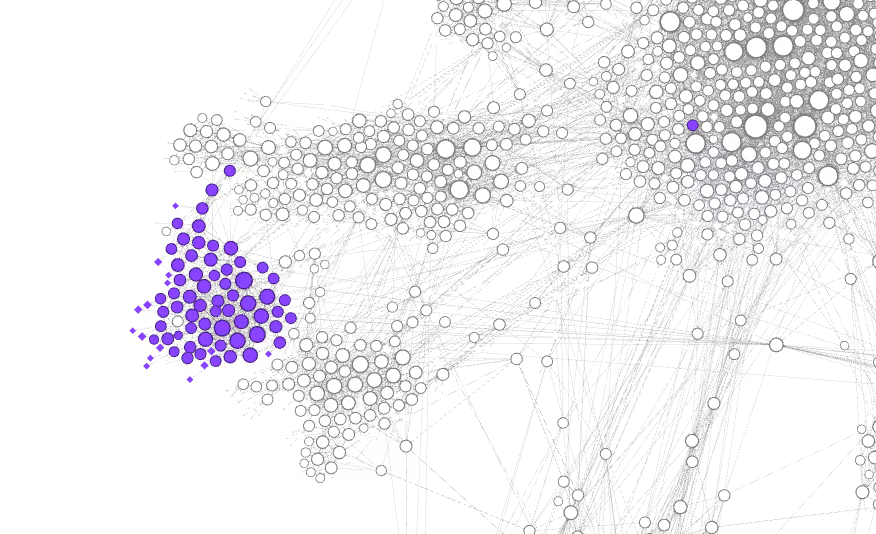

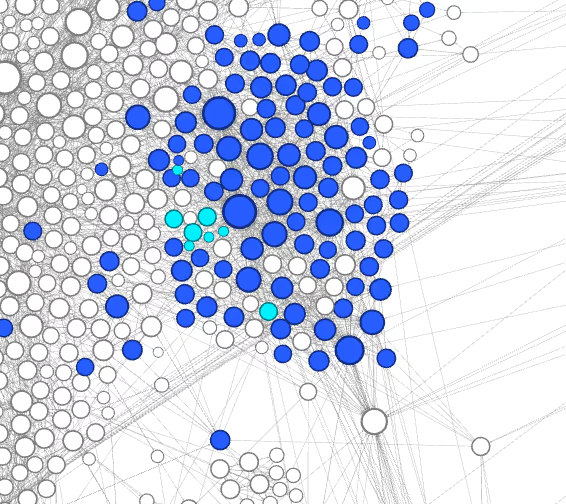

Occupied Territories

When a Ukrainian Telegram channel is structurally close to Russian pro-war propaganda, it often reflects either successful influence efforts from Russia or the activities of Russian-speaking Ukrainian bloggers like Oleksii Arestovich. However, “bridges” between Ukrainian channels and those focused on the occupied territories tell a different story – one of preserved informational ties with Ukrainian populations under occupation.

Local Ukrainian media and Telegram resources dedicated to cities and regions currently under Russian control – and still maintaining a pro-Ukrainian news feed – act as vital connectors between the Ukrainian cluster and the cluster of channels from temporarily occupied territories (ТОТ). These are likely read both by those who fled occupation and by those who remain.

Most of these “bridges” – local Ukrainian Telegram channels focused on life under occupation – connect Ukraine to newly occupied regions.

A strong example is the hub of Ukrainian Telegram channels focused on the city of Enerhodar – home to the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant (ZNPP). These include traditional local news accounts, as well as resistance-focused channels like Скелети Шевчика і Ко – named after a former collaborator and pseudo-mayor installed by occupying forces.

In the case of Mariupol, multiple Ukrainian channels remain active, including Маріуполь. Спротив and the highly effective Мариуполь Сейчас – which, with 132K subscribers and a consistent pro-Ukrainian feed, maintains strong connectivity to subscribers of occupation-linked channels.

Another notable case of effective resistance media is Крымский ветер. Launched in March 2014, it has consistently reported on developments in Crimea, including the movements of Russian troops and equipment, the locations of military units, explosions, and missile launches. This channel bridges audiences from Crimea, Ukraine, and Russian opposition.

Links Between TOT and the “Special Military Operation” Telegram Ecosystem

While the network reveals only a limited number of “bridges” between Ukrainian Telegram channels and those from the occupied territories, the connections between the ТОТ clusters and the Russian SVO hub are far denser. This reflects, in part, the systematic effort to build a centralized, top-down media landscape aligned with the Russian state’s vertical of power.

The territories occupied since 2014 are particularly tightly integrated – Crimea and especially the so-called “DNR” and “LNR.” These regions are not only home to media holdings like “Республиканский медиахолдинг” and “Луганьмедиа”, along with their affiliated outlets, but have also given rise to numerous war correspondents, brigade-linked channels, and frontline-focused accounts. Many of these were active even before 2022 and gained significant subscriber growth and official attention after the full-scale invasion, reinforcing their ties to the Russian propaganda hub.

Although Mariupol is structurally separated from the DNR cluster – likely due to its more diversified Telegram infrastructure – it maintains stronger ties with DNR-affiliated channels than with nationwide Russian outlets.

The newly occupied parts of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts are far less connected to Russia’s broader Telegram ecosystem. Instead, they are more tightly linked to each other, forming a subnetwork of shared resources. A telling example is the connection between the Crimean and Kherson clusters, built through local football clubs and regional championships – a form of cultural integration that serves Russia’s broader goal of absorbing newly occupied areas into its information and symbolic space, this time via sports.

Kharkiv, Kursk, and Belgorod

Since audience overlap is the key factor determining connections between Telegram channels, it is unsurprising that occupied regions tend to cluster together – often anchored by accounts affiliated with local administrations or their subordinate media outlets.

Similarly, it is expected that channels created in preparation for future occupation – like those targeting Kharkiv and its surrounding areas – remain tightly embedded within the Russian information space. These accounts reflect aspirational control, not actual territorial presence.

Russian Telegram channels such as ХарьковскаяРусь and Свободный Харьков illustrate this pattern. These accounts are fully integrated into the Z ecosystem and interconnected with channels focusing on how the war impacts Russia’s Kursk and Belgorod regions. Notably, they show no overlap whatsoever with major Ukrainian Telegram channels – not even with widely followed ones like Труха or Лачен пишет, which attract users from across Ukraine regardless of region.

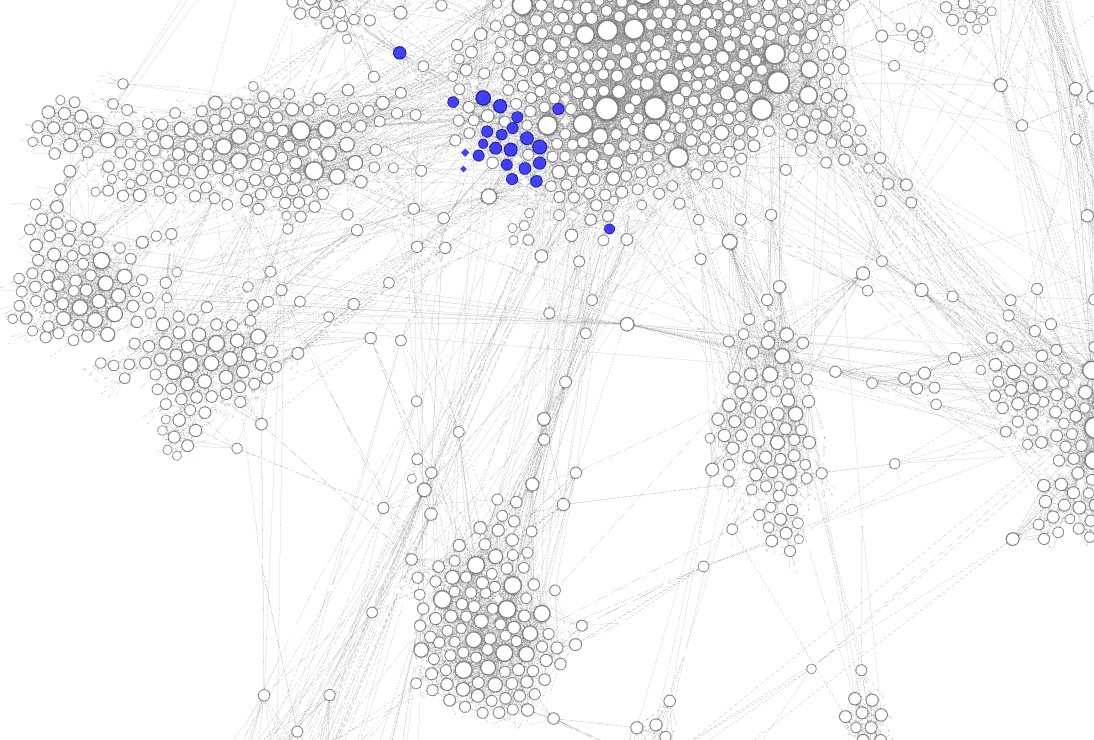

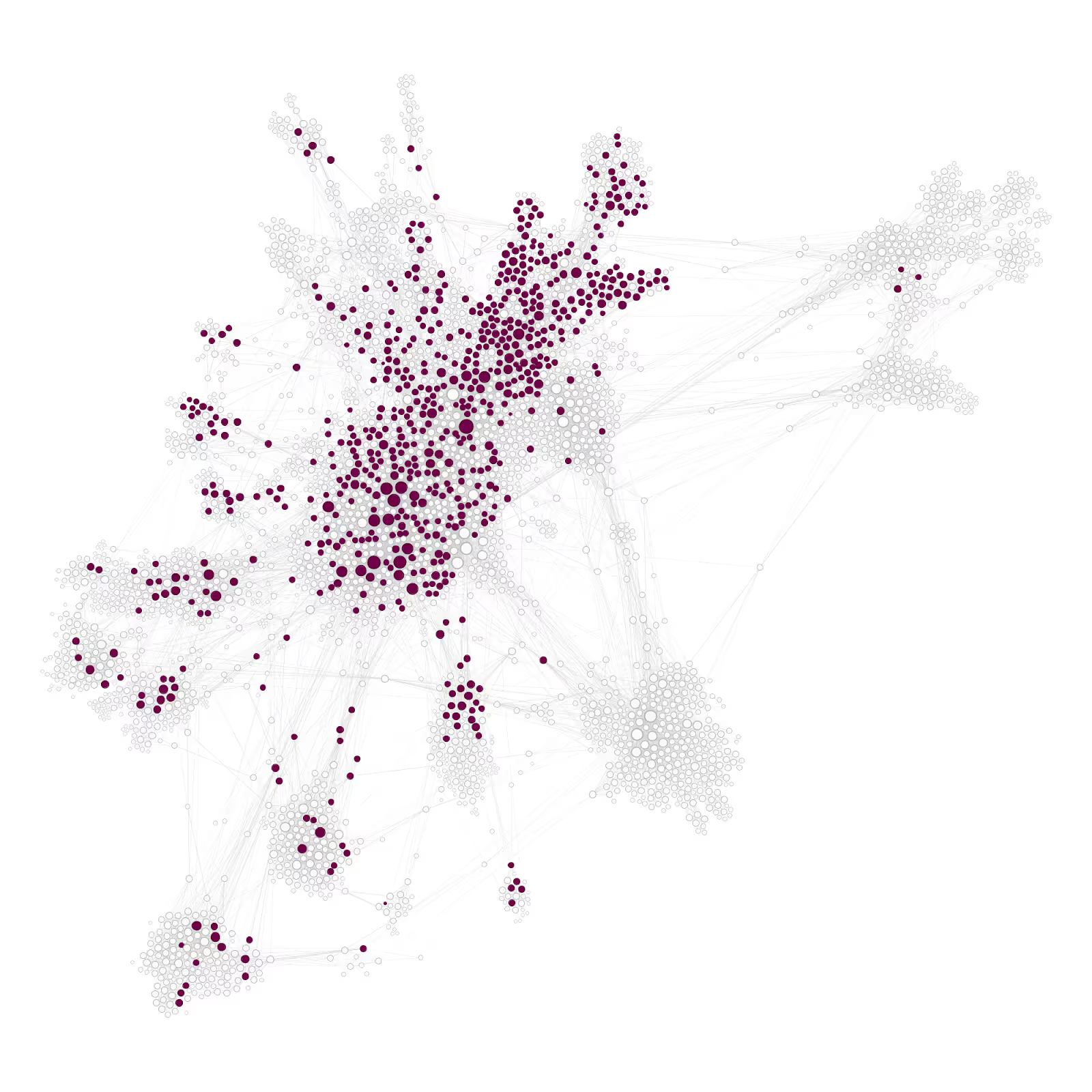

Russian Politics

Russian political actors – both individual politicians and party-affiliated channels – reveal that Telegram’s similarity clusters are shaped not only by geography but also by political alignment. This is particularly evident when analyzing channels linked to parties.

Despite often having modest subscriber counts, Telegram channels affiliated with Noviye Lyudi, KPRF, LDPR, and SRZP tend to cluster closely with one another. In some cases, ideological consistency appears to be a stronger binding force than audience size. For example, KPRF channels are frequently surrounded by a broader set of pro-communist and far-left Telegram accounts, even when those accounts are not formally affiliated with the party or party members.

What connects these politically aligned channels are meta-aggregators like МОСКВЫБОРЫ and МосГорДума 2024 / ГД 2026, which serve as hubs for parliamentary and local election-related content – effectively merging various party ecosystems into one shared cluster.

The exception is United Russia (Единая Россия) – the only major party whose affiliated figures and channels often appear outside the political cluster. This is largely due to its structural role: many Telegram channels representing the installed administrations in the occupied territories are officially affiliated with “main party”, positioning them not within a domestic electoral discourse, but within military and occupation-related clusters.

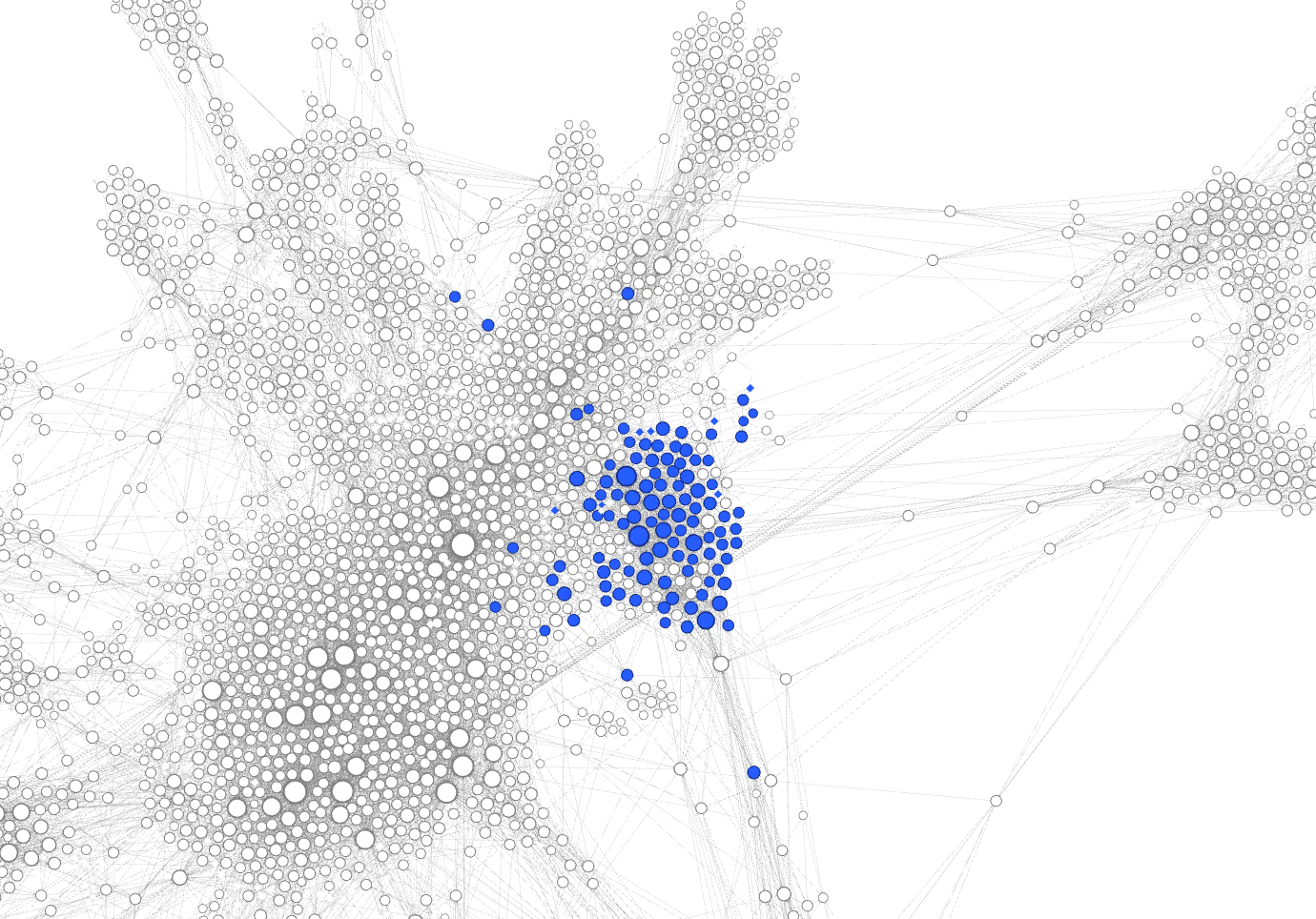

Russian Opposition

On the other end of the Russian information spectrum are the Russian opposition channels, which are structurally integrated into the broader Russian cluster. While they appear visually embedded within the network, clustering algorithms identify them as a separate group, based on the density and strength of internal connections. In other words, despite sharing some audience overlap with pro-government or other Russian media, these channels are more tightly connected to each other than to the rest of the Russian information space.

The most central and highly connected nodes in this cluster include: @ateobreaking (Ateo Breaking – 576K subscribers, 133 connections), @meduzalive (Медуза – LIVE – 1.2M subscribers, 120 connections), @nevzorovtv (НЕВЗОРОВ – 1.1M subscribers, 71 connections).

The last of these – @nevzorovtv – also acts as one of the shortest bridges between the Russian opposition cluster and the Ukrainian Telegram space, which aligns with his visibility as one of the most popular Russian commentators on Ukrainian YouTube.

Opposition channels are also connected to the broader Russian political cluster via @borisnadezhdin and his Moscow-based campaign office @center_msk. (Nadezhdin was a presidential candidate in Russia who publicly criticized the war and was ultimately barred from running by the Central Election Commission.)

A significant share of channels in the opposition cluster are labeled as foreign agents under Russian law.

This sharply contrasts with accounts registered with Roskomnadzor (RKN) – the Russian state media regulator. Under Russian legislation, Telegram channels with more than 10,000 subscribers must submit their data to RKN for official verification. The divergence between RKN-verified media and foreign-agent-labeled channels is stark – not just in status, but in structure, audience, and narrative alignment.

Hover over the point to see the channel name

.svg)

.jpg)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

-01-2.avif)

-01.avif)

-01.avif)

-01%25202-p-500.avif)