Russia Launches New War Recruitment Campaign, Promoting 'Safe' Frontline Jobs

Russia has significantly stepped up its contract service recruitment campaign in 2025, according to an analysis conducted by OpenMinds. The number of social media posts promoting contract service grew by more than 40% in the first half of the year. Drawing on social media monitoring, job-market data and war equipment loss records, data shows a shift from large-scale combat appeals to heavily promoted “non-combat” roles such as drivers – often advertised as safer but in reality used as bait to draw in recruits before reassigning them to frontline needs.

Since the start of the full-scale invasion, recruitment activity on Russian social media VK has peaked twice. First, in September 2024, following Ukraine’s counteroffensive in the Kursk region and a more than twofold increase in enlistment bonuses for signing military contracts. And again in February 2025, against the backdrop of peace talks, when many appeared to sign contracts in the hope of securing payouts and social benefits before a possible end to the war.

The surges in social media advertising for contract service closely mirror the rises in search queries on the same topic.

The latest recruitment drive also coincided with rising battlefield losses. Before Russian forces employed armored vehicles during their advances, but largely abandoned them in late 2024 and early 2025. By August 2025 they were relying mainly on small infantry assaults — a shift that likely drove higher casualty rates in the first months of 2025. Mediazona’s and BBC casualty database likewise shows sharply elevated Russian losses over this period, reinforcing the impression that higher recruitment was a response to heavier losses.

However, the advertising campaign has not translated into a comparable increase in actual enlistments. In May 2025, Vladimir Putin claimed that 50-60 thousand new soldiers sign contracts each month, and the Ministry of Defense announced that recruitment targets for 2025 had been raised. Yet calculations based on regional expenditure data point to much lower figures — around 30-40 thousand per month — and indicate that real recruitment fell in the first two quarters of 2025 compared to the final quarter of 2024.

The gap between declared targets and actual recruitment, combined with rising casualties, helps explain the aggressiveness of the current campaign. It also suggests that the authorities may resort to further incentives or other measures to meet their goals.

Drivers at war

A new feature of Russia’s recruitment campaign is the growing use of “safe service” language in advertisements. Phrases such as “Not storm units,” “Rear units,” “Quiet service,” “Easy service,” and “No front line” are now common, alongside promises of guaranteed placement in units specified by official assignment orders. These assurances suggest that recruits may be assigned to supposedly less dangerous roles rather than frontline assault units.

By July 2025, the share of recruitment ads using such phrasing had risen sharply – from a negligible level in previous years to about 20%.

Analysis of the specialisations and vacancies advertised on VK indicates that recruitment ads are gradually shifting away from large-scale, non-specialized conscription – the mass-mobilisation approach seen in 2022–2023, which appealed to collective solidarity and participation in the war — toward more targeted, specialised roles. Alongside promises of “safe service”, recruiters increasingly highlight non-combat assignments.

By April 2025, the number of ads seeking drivers alone exceeded the total number of ads for all combat specialties combined. Regional media likewise reported in July 2025, citing a local military commissar, that drivers were the most in-demand profession in the war zone.

This picture is further corroborated by data from the Russian job platform Headhunter. Over the past year, drivers accounted for 12% of specialised SMO-related postings, the single largest operational category. The only larger bucket (17%) was reintegration and veterans’ support services plus recruiters (e.g., job-placement officers, social workers, training/PR/legal staff at veterans’ centers). The heightened demand for these support roles aligns with the Kremlin’s push to integrate SVO participants into public life and institutions. A one-time data snapshot from Avito Job in August 2025 points the same way: non-combat roles dominated, with drivers at 20% and security guards at 18% of war-tagged vacancies.

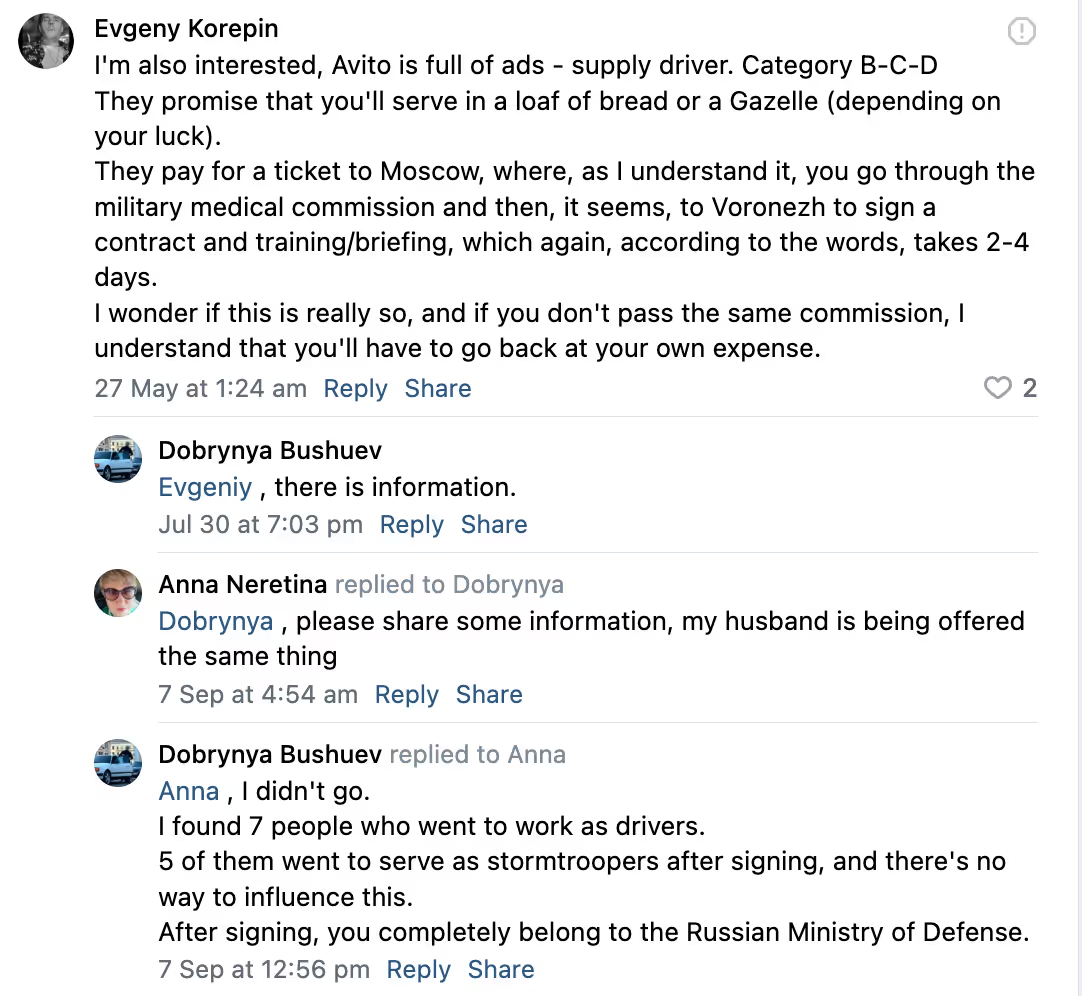

Safety trap

However, these vacancies often function as recruitment bait. They are posted by so-called “military staffing agencies” whose task is simply to lure new recruits with promises they cannot enforce. Applicants drawn in by the prospect of a safe, rear-area position sign a contract first and are only told later which unit they will actually join. In practice, commanders decide where contract soldiers are sent, regardless of the advertised role. One recruitment site even states openly that without an official assignment letter to a specific unit it is impossible to secure a driver post, since the commanding officer ultimately determines the placement.

Even when recruits are assigned the positions they were promised, such as drivers, this does not guarantee their safety. Posts on VK frequently report casualties among men recruited as drivers. One such post read:

“One of our UAZ vans that was delivering supplies to the 51st regiment was hit by an FPV drone. Unfortunately, the driver could not be saved — he was badly wounded by shrapnel and died from blood loss. Delivering provisions to the front line is becoming increasingly difficult, and the guys are taking great risks.”

Independent military equipment loss data compiled by the Oryx project underscores this vulnerability. Trucks and transport vehicles make up a striking share of Russia’s visually confirmed destroyed equipment. Between 2022 and 2025, they accounted for 15–30% of monthly losses in nearly half of all recorded months (median: 18%), at times rising above 40% — putting them on par with or even surpassing tanks and armoured fighting vehicles. By contrast, for Ukraine the category has been less prominent, with a median share of just 12% and only one in five months reaching the 15–30% range.

The trend in the chart shows how, since 2025, losses of infantry fighting vehicles have gradually declined while losses of trucks and other non-armoured vehicles have increased. Analysts link this shift to Russia evolving tactics: after heavy attrition of armoured assets, Russian forces increasingly rely on lighter vehicles and logistics convoys to support small-unit infantry assaults — a change that places these “non-combat” roles squarely in the line of fire.

Methodology

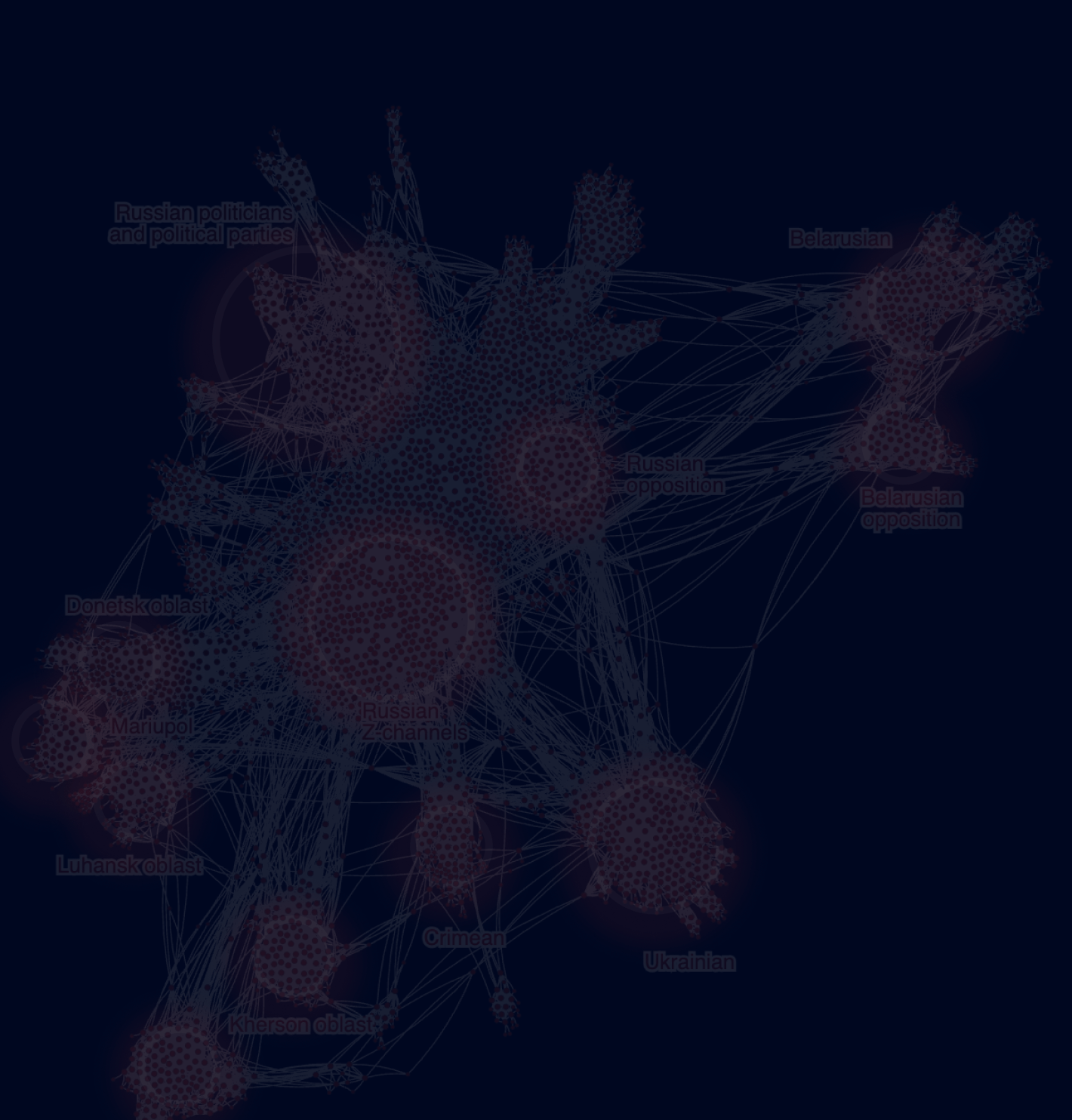

We collected and analysed data from several complementary sources to examine online promotion and recruitment related to Russian contract military service. Using the VK API, we extracted public posts on contract military service from the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022 through July 2025. The initial dataset was assembled through a predefined keyword list and then filtered with additional terms. We further applied a large language model (OpenAI GPT-4o-mini) to classify and retain only posts explicitly promoting contract service, resulting in a dataset of approximately 132 000 publications.

To capture labor-market recruitment signals, we also analysed 7 000 open or archived vacancies from headhunter.ru published between March 2022 and August 2025, as well as a one-time snapshot of 2 300 open vacancies from Avito Jobs in August 2025, applying the same prompting approach to extract and classify relevant military specialities.

In addition, we used Yandex Wordstat query data for “служба по контракту” and “контракт СВО” to measure public interest over time and incorporated military equipment loss data from Oryx using aggregated numbers from an open-source GitHub project.

.svg)

.jpg)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

-01-2.avif)

-01.avif)

-01.avif)

-01%25202-p-500.avif)